Poggio Bracciolini

You should place this name foremost in your memory regarding Italian history. Why might we need to remember this name? An epic poem and one of the most important texts of Western civilization. Poggio’s discovery, De Rerum Natura, quite literally changed the world.

Historians know little about Poggio’s early life. Records do not describe his birthplace, nor where he traveled in his early life. Eventually, he moved to Florence and became friends with two powerful Florentine leaders of the Florentine: Coluccio Salutati and Niccolò de’ Niccoli. These two influential men introduced Poggio to the elite of Florentine intellectual circles. As Poggio’s discoveries of ancient texts, their translation and transcription, became ever more known, so grew his reputation. He was a concise writer whose clear lettering became a recognized standard for all work done by such men.

A Scholar’s Proximity to Power

An Italian humanist scholar of the Fifteenth Century, Poggio was known not only for his interest in the recovery of ancient texts. He served seven Popes and proved his ability by rising from scriptor, to abbreviator, and finally to scriptor penitentiaries. As scriptor penitentiaries, he was as close to the Pope as possible. He recorded meetings, wrote notes for the pontiffs, and played the role of a confidant of high esteem. While serving Baldassare Cossa, the Antipope John the XXIII, Poggio saw the rise and fall of a brilliant man. Cossa was, also, a wily politician. During the Schism within the Catholic Church, Cossa usurped the Throne of St. Peter from a man who would, eventually and legally, retake that throne.

Poggio’s Discovery: De Rerum Natura

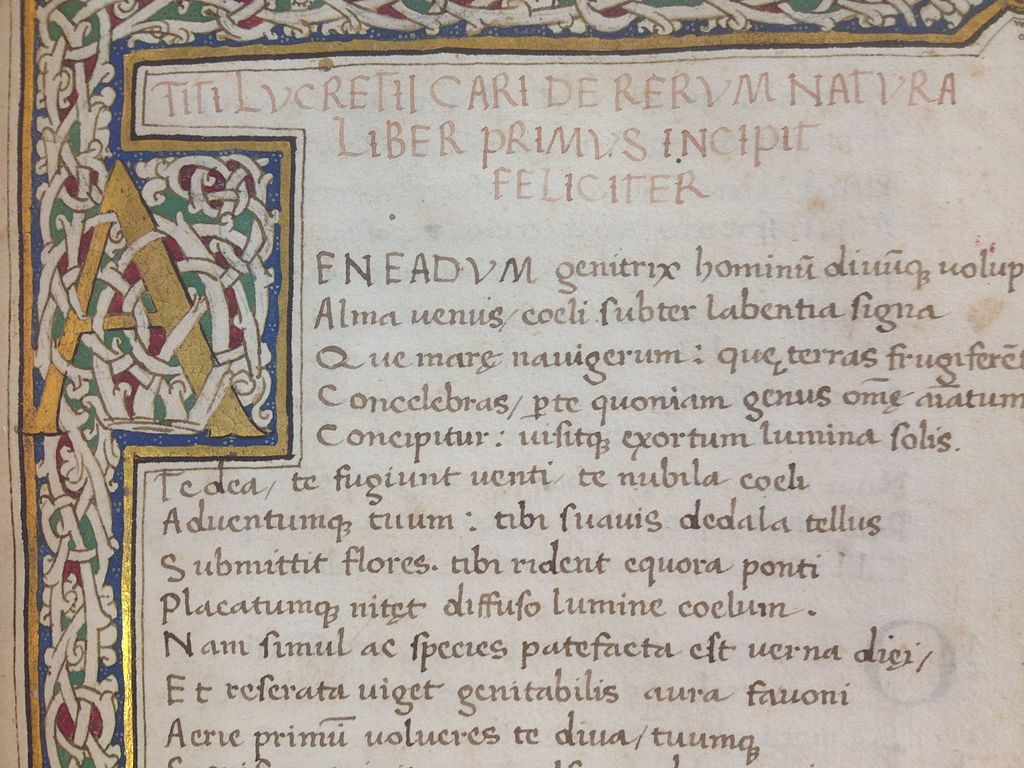

Poggio’s passion for locating ancient texts helped fund his work prior to, and during, his time within the Roman Curia. His passion never wavered. He searched for works of great ages, from Cicero to Livy to Lucretius. Of most significant note, he discovered a 7,400 line poem titled De Rerum Natura by Titus Lucretius Carus. Most historians believe Poggio made located this text at the Monastery in Fulda. His discovery, and the dissemination thereof, changed the world.

At a time when the Humanist movement was under siege by powers in the Catholic Church, the Epicurean idea that the most noble goal in life was to live a happy existence met with severe reprisal. The Catholic Church condemned as heretics, excommunicated, tried, and burned alive at the stake men who believed in the words of Lucretius’ complex and intellectually challenging work.

At the heart of De Rerum Natura lies a desire to spark a rebirth of intellectual life. Men like Poggio, as well as those who copied the text and disseminated it across Europe, sought to connect Renaissance thinking to the texts of ancient cultures. Among the ideas written by Lucretius, perhaps the most astounding is the concept of “atomism,” which suggested all things come from infinitely small particles, named atoms. This came from the mind of a man who wrote the 7,400 line poem in the First Century BC. Imagine, if you can, the impact of these words. Lucretius posited that something other than God created the form of all things. Rather, all life seemingly formed from random collisions of atoms.

Humanism, and the Renaissance

These early humanists sought to create a rebirth of intellectual life in Italy by means of a vital reconnection with the texts of antiquity. Their worldview was characteristic of Italian humanism during the Italian Renaissance. These humanistic views eventually spread over Western Europe and led the flowering of the Renaissance. Galileo, Calvin, Erasmus, Rabelais, Alberti, Boccaccio, painters like Masaccio, and innumerable others welcomed the ideals so clearly elucidated in De Rerum Natura. Even today, our form of government is based on humanist ideals of “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness,” as penned by men like Thomas Jefferson.

I highly recommend the 2012 Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Swerve, by Stephen Greenblatt, PhD. The work also won the National Book Award in 2011. This book expertly explains the legacy of Poggio’s search for De Rerum Natura. In my life, I have never read another book that so profoundly changed my understanding of the Renaissance, classical texts, and their role in our lives. It is a fascinating work of phenomenal research.